Jugalbandi

How are Hindustani and Carnatic music staying rooted in tradition while also adapting to the changing times?

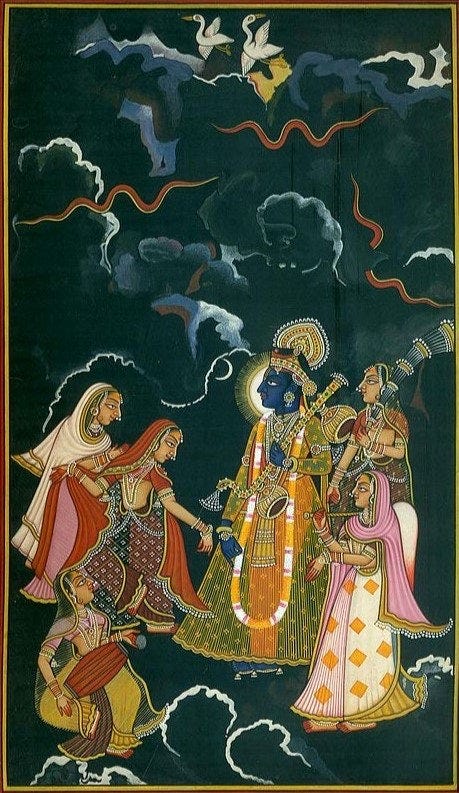

A Ragamala painting depicting the rainy Megh raga.

Legend has it that once during a performance when an industrialist’s wife ordered a paan, or a betel leaf delicacy, the doyen of Hindustani classical music, Kishori Amonkar, thundered, “Am I a kothewali to you?” (“am I a woman from a brothel to you?”). Famously reclusive and eccentric, music was her sadhna, or her spiritual practice. Why, then, did she perform her music for an illustrious audience rather than keep it entirely private? Was it an attempt at sharing one’s gift selflessly or was it an artist’s conceit?

The question may feel provocative, perhaps even offensive, to those rooted in Indian classical music traditions but it’s one an outsider will inevitably ask. That is, if and when an outsider decides to try and explore the music. Because, after all, selling oneself physically needn’t translate into a loose character or an impure spirituality. Not to take anything at all away from Amonkar, surely she understood just as much, having achieved spiritual bliss with her music?

Indian classical music is an incredibly vibrant and serious cultural tradition, composed of two schools— Hindustani, which is North Indian, and Carnatic, which is South Indian. While both originated from the same source, possibly in the Konkan region, they went decidedly separate ways during the Mughal rule in India. Where former developed in kingly courts, the latter evolved in temples. Where former sings of kings, nature, and love, the latter sings of Hindu deities. Where former encourages imagination, the latter privileges self-discipline. Where former allows for a musician to take flight in spirit to merge with the formless divine, the latter structures the musician towards the worship of a given divine. Where former has more religious and caste diversity, the latter is slightly less accessible in comparison. Where the former has shorter compositions known as Bandish, the latter has much longer ones known as Krittis. Where former sings in Hindi and Braj Basha, the latter is mostly Sanskrit and Telugu.

Both, however, work with certain ragas and talas. These are melodic tunes and rhythmic cycles. While Hindustani music adheres to the idea of a particular raga being more prominent during a particular time in the day, Carnatic music is not that concerned with it. While Carnatic music uses instruments like violin and Nadaswaram, Hindustani music doesn’t have similar instruments in its tradition. Last but definitely not the least, both traditions have an element of Bhakti, or worship. Where Hindustani music is the bhakti of the swara, or the musical note, Carnatic music is the bhakti of the deity. It is because of this that classical music in India is seen as a devotion.

Like day and night both the traditions are connected and separated. They are both going through similar issues in the 21st century where the filmy and pop music dominates. In their attempts to stay rooted and modernize lies their jugalbandi, or duet.

“At the beginning of 20th century, while there were many performers, Carnatic music had three main groups— Brahmins, Devadasis, and Isai Vellalars,” says Suresh, 54. Based in Bangalore, Suresh’s passion for music is illustrated by the fact that he calls himself Raaga Suresh on Twitter where he frequently posts about it. He is also the co-curator of Carnatic 101, along with Meera Sundar who is a professionally trained Carnatic musician. Set up in 2020, it is a place for them to discuss the particulars of various compositions for music enthusiasts.

While he works in the IT industry, his love for music goes back to his childhood when he used to listen his mother sing. She didn’t sing professionally but it was enough to get him hooked for life. Music was a part of the household and the mother-son duo would discuss the ragas often. Having carried the passion all his life, he is careful with the history of music too.

“At the time, most musicians were looked down upon and amongst women, only the Devadasi community performed on stage,” he explains. Following the Madras Devadasis (Prevention of Dedication) Act in 1947, the community found it hard to survive and eventually faded. “Nadaswaram and Thavil Vidwans, many of whom hailed from Isai Vellalar community, were patronized by temples,” he adds. While their compositions inspired many vocalists, their community too faded away due to dwindling patronage from the wider audience. “The tradition still continues but it’s not what it was in its heyday,” Suresh says.

With both of these traditions fading away, Carnatic music started seeing more and more Brahmin musicians as the community held important positions in music sabhas, or regularly organized music events. While other castes, such as the Chettiars, were great patrons of music, they did not actively pursue it.

On the other hand, the Hindustani music is a Gharana based system. It means that there are a lot of sub-traditions, each having its own style and maestros. Many well-known gharanas today were established by Muslim musicians and until about 1950s, the biggest names amongst male vocalists were Muslims such as Faiyyaz Khan of Agra gharana, Abdul Karim Khan of Kirana gharana, Alladiya Khan of Jaipur Atrauli gharana, and more. In recent decades, however, the tradition has become dominated by Hindu musicians such as Bhimsen Joshi, Kumar Gandharva, and Mallikarjun Mansur to name a few. While the musicians of this tradition are spread across the country, Maharashtra and North Karnataka are currently its epicenter.

Amonkar, who passed away in 2017, was a Maharashtrian Hindustani classical musician from the Jaipur gharana, having been trained by her mother. Two other legendary female musicians were M.S. Subbulakshmi and Begum Akhtar. The former, a Hindu, was a towering personality of the Carnatic tradition, the latter, a Muslim, was the queen of the Hindustani music. Both, however, had associations that Amonkar may have found to be unsavory, given her outburst. While Subbulakshmi was the daughter of a Devadasi, Akhtar was born to a courtesan. Interestingly, both starred in movies too at the beginning of their careers.

So, how is one to understand the world of Indian classical music? That music is a sadhna, i.e., a spiritual discipline where one has to weather most difficult challenges is something one hears all too often. But what exactly does it mean, more so in an age of Instagram and Tik-Tok? Chaitanya Tamhane’s The Disciple, now streaming on Netflix, explored that in a way that was almost “under-glamorized”, as Aditya Dipankar puts it. Dipankar, 36, lives in Mumbai which is also the setting for the movie. While he studied graphic design at National Institute of Design in Gujarat, his life has been majorly defined by music right from his childhood. “I started playing tabla at five [and] singing around the time I was in college,” he says, sharing that now he plays the saxophone as well. He is also the founder of a music streaming app, Ragya, which is exclusively dedicated to the Hindustani classical music.

A screenshot from Ragya’s mobile app.

Dipankar used to play in a college band, Manthan, performing at various premier educational institutes in Bangalore. However, as of last few years, he is beginning to pursue it more sincerely. Like the main character of the movie, he too developed a close personal relationship with his guru Vijay Sardeshmukh, even moving cities to learn under his tutelage. “I received only about four-five lessons from him, most of what I learned was through the early morning or evening walks that we used to take,” he says. His guru lived in Pune and accepted him as a disciple after listening to him. The guru-shishya parampara, i.e., the teacher-student tradition, is at the heart of much of Indian classical music.

While he eschews Bollywood music, he supports fusion music which seeks to bring together the classical and the modern. “There are a handful of bands that get fusion right, such as Advaita and Mrigya,” he says. He also informs that a lot of A.R. Rahman’s and Amit Trivedi’s music is based on ragas and so when people enjoy that, they are actually enjoying a derived form of Indian classical music.

Dipankar credits his guru for not only helping him shed a variety of musical influences to find his own voice but also in enhancing his sensitivity. “Once we were on a walk and guruji took a champa flower,” he starts to explain with an example, “and he said that there is no human-made scent that can compete with this flower’s scent. With that in mind, meditate on the creator of this flower and its scent,” he finishes. His guru’s simplicity won him over when he first saw him appear on a documentary Koi Sunta Hai and decided that he wanted to embody that saralta, Hindi for simplicity, in his life too. He launched the Ragya app in 2020 and today it has over seven lakh unique listeners. As a designer who prefers minimalism and is influenced by apps such as Spotify and Idagio, he wanted to keep it simple with his app too. When you launch the app, it will automatically play a composition that is in a raga appropriate for the that particular time. “You don’t have to think about what to play and that also removes the barrier to access for a lot of new listeners,” he explains.

Ragya not only hosts the music of many legends, living and deceased, but also gives a platform to new and undiscovered artists. While one can play a certain set of compositions for free, the true potential of the app is unlocked in its paid subscription mode. To support the artists, Ragya pays the artists based on how their compositions do and a dividend from their subscription revenues. “We are disrupting the industry by making a democratic platform for the artists,” he says. Unlike the big labels that offer a one-time meagre payout to the artist but earn from that music for life, Ragya wants to create a legitimate and stable earning source for the artists.

“I often see artists posting on Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube because they’re looking for audience engagement,” he says. “But if I listen to a rendition on YouTube, after a couple of video the algorithm will take me to Bandish Bandits to perhaps eventually more popular music which might have little to do with classical music,” he explains. Because the system is engineered to lead the listener to the most popular and biggest source, talented upcoming artists struggle with being discovered.

But both The Disciple and Amazon Prime’s Bandish Bandits also touch upon something that is less freely discussed— the humanity of musicians, for better and worse. Both bust the myth of musicians as being saintly, almost godly figures, who must be worshipped by one and all. Instances of abuse and destroying careers of other musicians abound the industry, most notable examples being Gundecha Brothers and Ravi Shankar. For a discipline that stresses so severely on spiritual purity, it is perhaps hypocritical to tolerate or enable reverence and deification of musicians who have exhibited such weaknesses and meanness of character. While no one doubts that most musicians approach their craft sincerely, not addressing this issue leaves a bad taste in the mouth about that which is supposed to be divine through and through. “A lot is accepted and normalized in this reverence [and] we are trying to change that with Ragya,” Dipankar says. “[For starters], we don’t use honorifics such as Pandit or Ji when we list the names of musicians— it’s just the first name and last name,” he adds.

It’s a step towards modernizing of what is traditional but how far can one go? From Hindustani musicians being asked to play ragas irrespective of the time of the day to those making rap out of the deity-based Carnatic music, it would irritate the purist but may also be akin to feeding fast-food to the uninitiated listener by modernizing without retaining the essence of the traditions. “When the audience doesn’t want to put in effort, there already exists music for them such as filmy music and that’s fine,” says Suresh. “But there are certain artforms that demand effort and classical music is one of those,” he says. If you were listening to K.J. Yesudas, he says, you may catch on to it even as a beginner but if you were listening to T. Brinda, it may take you over twenty years to understand her music.

Suresh explains that Carnatic music has modernized in terms of style, tones, and innovations, even to the point of changes in what the musical tradition was and is at its core. “There is also more access, you can attend many free concerts or listen to them online,” he says. As with Hindustani music, he admits that there are gatekeepers on the Carnatic circuit too. A determined musician may manage to navigate these barriers but in doing so, they may also overwhelm the others. He feels that Carnatic musicians are unable to earn as well as Hindustani musicians, partly because the latter has a broader appeal. To supplement their incomes, they sometimes teach music to students, both in India and abroad, via Skype or a similar online platform, earning anything between $15 to $40 per hour. Learning early is the key to understanding the tradition, after all. “It can be harder to appreciate Carnatic as compared to Hindustani music,” he says, “a lot of people who enjoy this have grown up with it.”

Both traditions are undergoing their churning of modernization and rediscovery in a variety of ways, given their individual challenges. It remains to be seen what kind of melody this jugalbandi will yield in years to come.

Superb!